The Mystery of Flight MH370 / Telegraph Magazine

Nobody disputes the initial facts – not even Florence de Changy, a French journalist whose new book on the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 is about to revive the greatest mystery in aviation history.

At 00:42 on 8 March 2014, MH370 took off from Kuala Lumpur International Airport bound for Beijing. On board the Boeing 777 were two pilots, 10 flight attendants and 227 passengers of 14 different nationalities. They included Chinese labourers and package- holiday tourists going home, a group of calligraphers, a stuntman who was working on a new Netflix series, and 20 employees of a US electronics company. Five were children.

At 01:01 MH370 reached its cruising altitude of 35,000ft as it flew north over the South China Sea. At 01:19, as it left Malaysian airspace and crossed into Vietnam’s, Zaharie Ahmad Shah, the captain, radioed back the last words heard from the flight: ‘Good night Malaysian Three Seven Zero.’

Normal procedure is that the aircraft should then declare its presence to Vietnamese air traffic control but no call came. A minute later the plane’s transponder – its link to air traffic control – cut off.

Almost immediately its Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS), which transmits technical information about flights, ceased working too. Thereafter MH370 simply vanished.

It issued no distress call. It had displayed no sign of trouble. On a clear night, in good flying conditions, one of the world’s safest aircraft, operated by an airline with an excellent safety record, disappeared in a region full of civilian and military radar stations and heavily monitored by satellites.

Seven years later, incredibly, its fate remains unknown.

For a week, scores of ships and planes searched the South China Sea for traces of the missing plane. Then, on 15 March, Najib Razak, Malaysia’s then-prime minister, announced startling new findings. He said that an aircraft believed (but not confirmed) to be MH370 had been detected suddenly changing course after entering Vietnamese airspace.

He also advanced the theory that these movements were ‘consistent with deliberate action by someone on the plane’. That is the point at which de Changy starts taking issue with an official narrative which she dismisses as a ‘fabrication’.

According to that narrative, Malaysian military radar had spotted a plane climbing and descending steeply as it flew back across the Malay peninsula, veered up the Malacca Strait and round the northern tip of Sumatra into the Indian Ocean.

Thereafter Inmarsat, a satellite telecommunications company, picked up occasional electronic ‘pings’ from the aircraft. From those pings, scientists calculated that MH370 may have flown six hours southwards after rounding Sumatra before crashing into the sea more than a thousand miles west of Australia, having presumably run out of fuel.

The narrative was subsequently reinforced by the discovery, a year later, of debris apparently belonging to MH370 washed up on the beaches of southern Africa and the island of Réunion on the far side of the Indian Ocean.

Inmarsat’s calculations triggered the most expensive search in aviation history. For nearly three years, at a cost of well over £100 million, more than 100 ships and dozens of aircraft from 24 countries scoured 120,000 square kilometres of ocean. They found nothing except a pair of 19th-century shipwrecks.

In 2017 the underwater search was called off and the Australian Transport Safety Bureau, which coordinated it, issued a report that said it was ‘almost inconceivable’ that a plane could simply go missing in the modern age.

In 2018, to the dismay of the victims’ relatives, a final report by an official investigation team, comprising experts from Malaysia, Australia, the US, China, Britain, Indonesia, Singapore and France, likewise failed to explain MH370’s disappearance, though it did not rule out ‘unlawful interference by a third party’.

Conspiracy theories thrive in vacuums. This case was no exception. Fuelled by the lack of hard facts and by the opacity, contradictions and apparent inconsistencies of the authorities, they proliferated.

Some were manifestly crazy. MH370 had vanished into a black hole, or been captured by aliens, or seized for use in another 9/11-style attack. The missing plane was said to be in Somalia, Kazakhstan or North Korea, or rumoured to have been destroyed to eliminate witnesses to an organ-harvesting scheme run by a top Chinese official’s son.

Other theories were superficially more plausible. A terrorist hijacking was a leading contender, but why would the captain in his fortified cockpit not have issued any sort of alarm? Why would the terrorists not have claimed responsibility or made demands? Why would they fly the plane to the middle of the sea, not an airport? And none of the passengers were deemed likely hijackers.

Another possibility was a fire or some sort of catastrophic accident, leading to a lack of oxygen that swiftly killed all those on board. Certainly there was a consignment of potentially flammable lithium-ion batteries in the hold. But the cockpit had its own emergency oxygen supply, and would the plane really have followed the erratic course it did on automatic pilot?

The leading theory, encouraged by the former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott, who was in office when MH370 vanished, was that the pilot was suicidal and deliberately crashed the plane into the sea. ‘I want to be absolutely crystal clear, it was understood at the highest levels that this was almost certainly murder-suicide by the pilot,’ he told a Sky News documentary last year.

Australian pm Tony Abbott declared the crash ‘murder-suicide’ CREDIT: AFP via Getty Images

Zaharie Ahmad Shah’s marriage was rumoured to have been in difficulty. A flight simulator in his house had allegedly been used to plot a course to the southern Indian Ocean. But investigators concluded that the data wasn’t incriminating, and the official investigation found no evidence that Zaharie, who had an exemplary 16-year record of flying Boeing 777s, was suffering mental health problems.

If he was bent on suicide, why would his co-pilot, Fariq Abdul Hamid, not have tried to stop him? And unless he craved one final ‘joyride’, why would he not have crashed the plane immediately?

De Changy, 53, is no crank. Personable and articulate, she is a reputable journalist who has covered South East Asia for Le Monde and Radio France for two decades. She previously lived in Malaysia for three years and is now based in Hong Kong.

The day MH370 went missing she was visiting her childhood home in Verona and heard the news on the radio of her rented car. ‘My first thought was, what a shame I’m not nearby because there was a chance Le Monde would send me,’ she recalls in a Skype call from her houseboat in Hong Kong.

The day she returned to Hong Kong, one week later, Najib Razak announced that MH370 had been deliberately diverted. Before she could unpack, Le Monde dispatched her to Kuala Lumpur. At that point, she says, ‘You have no reason to doubt what they told you… it’s natural to be gullible’.

French journalist Florence de Changy, whose new book delves into the mystery of MH370 CREDIT: John Javellana

On the first anniversary of the plane’s disappearance she wrote a long article in which she was considerably more sceptical about the official narrative. That led to a book, published in 2016, in which she cautiously suggested the lost plane might not be in the Indian Ocean at all, but in the South China Sea where it was originally presumed to have crashed.

‘I was almost embarrassed with what I was coming up with,’ she says. ‘I didn’t want to go there. You know it’s very bad to be a conspiracy theorist.’

But the book prompted people to approach her with new information and before she knew it, she was ‘down the rabbit hole’.

Since then, she has visited at least 15 countries on four continents in her quest for the truth. She has interviewed hundreds of people, from fishermen in the Maldives who claimed to have seen a huge plane labouring low and noisily over their remote island early on the morning MH370 went missing, to a former officer of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army who shared her suspicion of the official narrative.

‘The whole narrative is an insult to human intelligence,’ she says. ‘It’s really crazy. It doesn’t make sense to tell the world that we’ve lost track of a Boeing 777… If, as a journalist, I don’t react to that then I might as well go and sell socks or ties.’

De Changy’s first and unequivocal contention in her new book, The Disappearing Act, which is published next week, is that indeed MH370 went down in the South China Sea, as first suspected, not thousands of miles away in the Indian Ocean.

She points to the lack of a single radar image conclusively showing the plane heading west then south, even though two major military exercises were taking place near its alleged route. In her book, she suggests the few images that do exist might have been of other planes, and that the erratic flight pattern of the plane said to be MH370 exceeded the performance capabilities of a Boeing 777.

Thereafter, she argues that ‘no one – not one single person, not a radar, not a ship, not a satellite, not a military base, not another plane – saw MH370 above the southern Indian Ocean’, and that the largest search operation ever mounted ‘failed to find a shred of evidence’ that it crashed there.

And what of those electronic ‘pings’ that indicated the plane had continued flying for hours? ‘This despotic set of pings had, I felt, imposed its version of the truth on the whole world,’ she writes. She suggests that they might have been generated in some other way, possibly by other planes.

As for the ‘avalanche of debris’ discovered on the shores of Réunion and southern Africa, she insists that the supposed ‘finds’ amounted to collective wishful thinking and had nothing to do with MH370. She writes: ‘“Highly likely” and “almost certain” were very soon the buzz phrases used to qualify any kind of debris collected in the south-western part of the Indian Ocean that bore even the remotest possibility of having come from MH370.’

The official narrative, de Changy concludes, ‘has every semblance of a decoy’.

It’s quite a claim. But she’s not finished. ‘Almost seven years after the loss of the plane, the authorities’ version of what happened to MH370 is even less credible than when it first surfaced,’ she writes. ‘The primary function of the sub-sea search led by Australia in international waters was simply to keep people’s attention focused somewhere, just like the diversion that any magician employs to mask his sleight of hand.’

De Changy then marshals the evidence supporting her contention that the plane went down in the South China Sea. It includes contemporary Vietnamese news reports to that effect; a mysterious message from Vietnamese air traffic control to its Malaysian counterpart at 02:40 saying ‘the plane is landing’; Chinese media reports of an SOS from the pilot at 02:43 requesting an emergency landing because his plane was disintegrating; Chinese satellite images of apparent debris littering the water; and two large oil slicks allegedly spotted off Vietnam’s coast.

She says villagers and fishermen along Malaysia’s north-eastern coast reported unusual sights and sounds including explosions early that morning, and a New Zealand oil worker, Michael McKay, reported seeing a ‘burning plane’ in the sky from his platform off the southern tip of Vietnam.

Evidence was ‘ignored, dismissed, denied or just erased’, she claims. High-resolution satellite images of the South China Sea that might have identified floating debris were later mysteriously unavailable. An unedited transcript of all the exchanges between MH370 and Malaysian air traffic control during its 42 minutes of flight was never published.

De Changy also claims that, in a change from usual practice, movements for ships of the US Seventh Fleet, based in Japan, were not published on the website of US Pacific Command for a month each side of MH370’s disappearance.

Having interviewed Zaharie’s friends and relatives, she also asserts that he was the ‘target of a relentless smear campaign’ and ‘never had the slightest of deadly intentions’. He was a ‘perfectly sane and happy pilot, operating at the top of his game’. If he was the culprit, he did ‘what no one else has ever managed to do: lose his plane and all those on board for ever, without leaving the slightest trace’.

De Changy cannot be faulted for her tenacity, but three aviation experts who have followed the case gave little credence to her claim that MH370 lies in the South China Sea. ‘I think it’s pretty far-fetched,’ says a former senior British government official who declined to be named.

‘This is just nonsense. We know where the aircraft went down,’ says Duncan Steel, one of several independent scientists, engineers and mathematicians who pooled their expertise in order to try to solve the mystery.

David McMillan, former chair of the global Flight Safety Foundation, allowed some ‘room for doubt’ given the lack of hard facts, but added: ‘The broad consensus is that people were looking in pretty much the right place.’

Relatives of the victims were similarly sceptical. ‘As of now, the only evidence we have is that the plane ended its flight in the southern Indian Ocean,’ says Grace Subathirai Nathan, a Malaysian lawyer whose mother was on board MH370. Journalists like de Changy are free to pursue their investigations, she adds, ‘but it’s not easy to constantly have to talk about it, constantly have to remember it'.

KS Narendran, a development consultant, who lives in Chennai, lost his wife on MH370. In a Skype call, he said of the official narrative: ‘It doesn’t add up. It doesn’t square up. There’s nothing conclusive about it.’ But neither did he endorse de Changy’s theory.

De Changy’s hypothesis also begs the question: why would anyone want to conceal the fact that MH370 crashed into the South China Sea, if indeed it did?

In the book’s final chapter she attempts to answer that. She believes that the story was designed to detract from ‘a massive blunder of unspeakable proportions’ – namely that the plane was shot down. And she proceeds to sketch out a hypothetical scenario which, despite some ‘holes’, she believes to be ‘80 per cent’ correct.

In it, MH370 was carrying stolen technology, perhaps a powerful spying device. The US had to stop that precious load reaching China. It dispatched two Awacs planes to jam MH370’s communication systems, effectively rendering it invisible, then force it to land at a nearby military airport where the cargo could be removed. When Zaharie refused to land, the Americans shot the plane down before it entered Chinese airspace.

‘The shooting down could have been a blunder, but it could also have been a last resort to stop the plane and its special cargo from falling into China’s hands,’ she writes.

De Changy contends that the US and China had obvious reasons to conceal the truth, and that her scenario, though hypothetical, is ‘based on a cluster of solid clues’. She goes on to claim that stories were planted to promote the official narrative.

Is this the wildest conspiracy theory of all? Is de Changy merely the latest MH370 obsessive to be sucked into what she calls ‘the dark recesses of the labyrinth’ of this mystery?

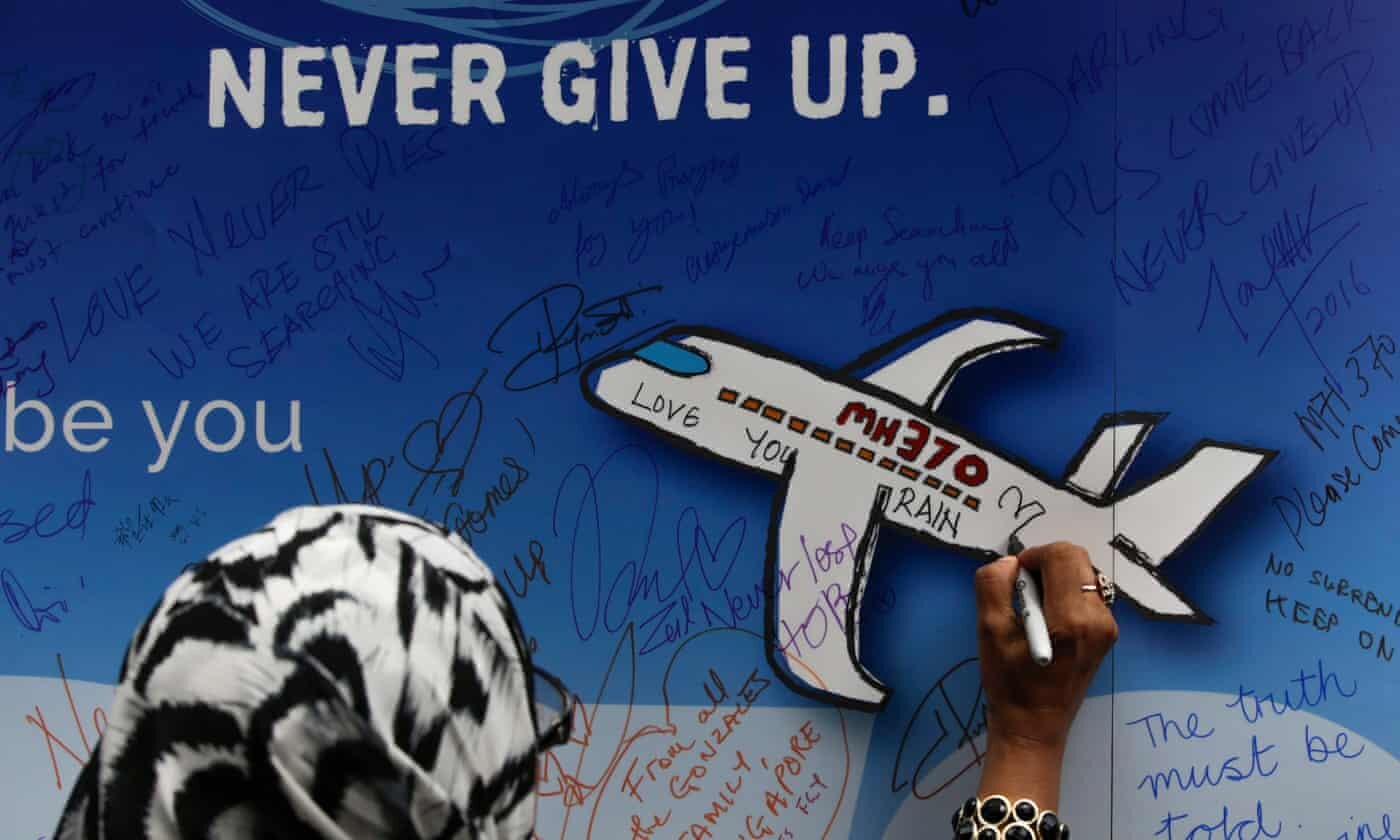

A Malaysia Airlines employee writes a message of prayer at Kuala Lumpur airport a week after the crash CREDIT: AFP via Getty Images

The relatives of some victims are reluctant to believe it. Grace Nathan said it sounded ‘quite far-fetched’, adding: ‘It’s highly impossible all this happened in a short span of 20 minutes, completely unnoticed.’ KS Narendran observed that ‘there are easier ways for a government such as the US to deliver things that it wants to, or eliminate people if it chooses to’ than shooting down a commercial airliner.

Moreover, if de Changy’s scenario were true, hundreds of people in many different countries and organisations would be complicit, and the secret would surely have spilt by now.

De Changy acknowledges that, but says she is confident people will yet come forward with the final bits of the jigsaw. ‘I’m almost there,’ she insists.

The official investigation has long concluded and only a secretive French judicial investigation continues into who or what killed four of its citizens on that flight. But in a final push for the truth, de Changy dedicates her book to ‘all those who know something more’ – those ‘who are duty bound to reveal their share of the truth and end the terrible distress of the victims’ loved ones’.