Saving the World’s Coral Reefs / Telegraph Magazine

“It’s going! It’s going!,” someone shouts.

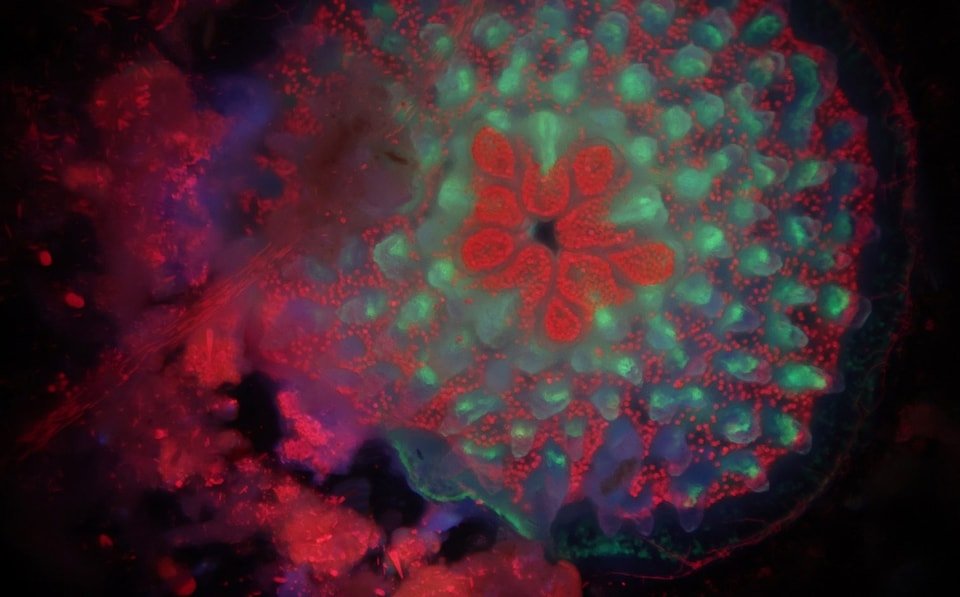

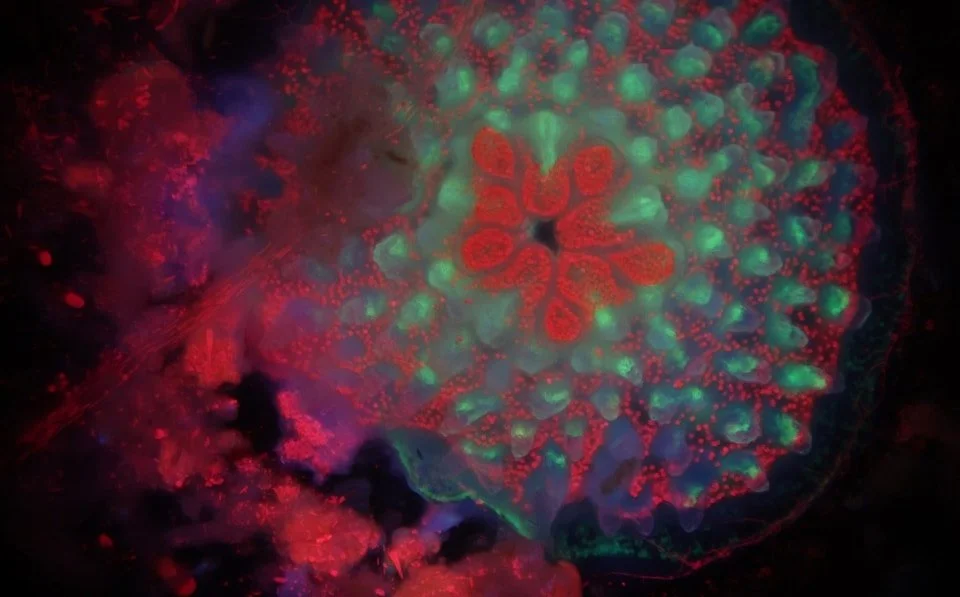

We hurry up a short flight of steps to an illuminated aquarium tank hidden behind a blackout curtain. There we witness the start of what my host, Jamie Craggs, calls “the magic”, and it is a strikingly beautiful sight.

On the floor of the tank a small coral ‘tree’, around six inches high, is beginning to spawn. The polyps on its branches - each a living animal - are releasing what Dr Craggs aptly describes as an “explosion” of tiny, pinkish, luminous balls, little bigger than pinheads. Thousands of them float slowly and serenely to the surface against a deep blue background.

It is a rare privilege to see a coral spawn: the process happens just once a year, and generally lasts less than 30 minutes. I watch, mesmerised, but Craggs has work to do.

Each ball, or ‘bundle’, contains as many as a dozen eggs, and thousands of spermatozoa. He begins swiftly collecting the bundles with a pipette tube, then rushes them down the steps to a tiny laboratory before they burst.

There two biologists will attempt - for the first time in Europe - to cryogenically freeze the sperm so the corals can potentially be reproduced a hundred or a thousand years hence should today’s coral reefs be destroyed - as seems likely - by climate change.

Meanwhile Craggs and his assistants will attempt to fertilise the eggs with the sperm of other coral species in order to develop hybrids better able to withstand the steadily warming oceans.

In short, it comes down to this: if there is any hope of saving the world’s beleaguered coral reefs it emanates to a surprisingly large extent from the pioneering work being carried out here in the unlikely confines of a tiny, basement aquarium in the small Horniman Museum in Forest Hill in deepest South London.

Founded by a Victorian tea trader 123 years ago, the museum is a 50-minute ride from Trafalgar Square on the 176 bus - and about as far from a coral reef and turquoise sea as it is possible to be.

****

Craggs is the aquarium’s hugely enthusiastic principal curator. Born 48 years ago in Brightlingsea on the Essex coast, he spent much of his youth in, on or beside the North Sea - crabbing, rock-pooling, swimming, sailing and windsurfing. He acquired his first fish tank at the age of ten. During his teens he graduated from keeping frogs to goldfish to tropical freshwater fish to marine animals.

He studied ecology and marine biology at Plymouth University, spent three months researching coral reefs in the Philippines, and another 18 as an underwater cameraman filming reefs off Borneo. From the London Aquarium, where he was the head aquarist, he moved to the Horniman in 2008, and has since devoted his professional life to his quest to save the world’s endangered corals.

“Corals are such important animals in our ecosystem,” he says. “They’re incredibly diverse habitats. One square metre of coral reef contains as many different types of animals as a whole hectare of Amazon rainforest.”

But, he adds: “As a result of climate change we’re losing those corals. They’re in desperate need of help.” Half are already in trouble, including Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. As many as 90 per cent will be afflicted if the world heats up by another 1.5 degrees - the best-case scenario foreseen by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. An increase of two degrees would mean practically none surviving in anything like their present form.

In 2012 Craggs launched Project Coral in what is essentially a long, largely windowless corridor on three levels that is hidden away behind the aquarium that the Horniman’s visiting public sees. Its walls are lined with tanks full of corals, mostly hidden behind blackout curtains, and a tangle of pipes and electric cables. It is so narrow that he and his three assistants have to perform what they call the ‘Horniman Shuffle’ to get past each other. “It’s not a cutting edge facility, that’s for sure,” Craggs laughs.

He nonetheless enjoyed a swift and seismic breakthrough. That first November he spotted a tweet from a Fijian diving company offering customers the chance to watch corals spawning at sea two days later. From that exact date he managed to work out the lunar cycles, day lengths and water temperatures in the months leading up to the spawning, then crudely replicated them in the Horniman’s aquarium.

The following year he and his team became the first researchers in the world to induce a captive coral to spawn not by accident, but purposefully and at a time of their own choosing.

It happened at 11.30 one September night. “It was amazing, absolutely phenomenal,” Craggs remembers. “There was a lot of whooping and cheering, and I knew at that moment exactly the potential of that.”

He gradually polished and refined the technique. He put probes on coral reefs, studied Nasa charts and amassed data on sunrises, sunsets, lunar cycles and nutritional inputs from different parts of the world. He fed that information into computers and produced a programme for each of the aquarium’s 50-odd species of coral, garnered from around the world, that would exactly replicate their natural environments.

Above each tank adjustable LED lights now simulate the rising, setting and arc of the sun each day. Half ping pong balls struck over other lights do the same for the moon. The water is ordinary London tap water, but with the impurities filtered out and salt added to produce exactly the right levels of salinity. “We don’t have the luxury of the beautiful tropical ocean right on our doorstep so we start from base tap water,” says Craggs.

By manipulating those conditions, by pushing lunar and solar cycles forward or back, Craggs and his team have since managed to manoeuvre all the aquarium’s corals on to the same ‘coral time’. The corals all now spawn within a week of each other, and at a precise time of the team’s own choosing.

In addition to that, Craggs has tricked the corals into spawning at the start of the working day by making them think it’s sunset, which makes life far easier for researchers. He points to a red digital clock on a wall. It shows what he calls ‘coral time’. “To them it’s 6.53 at night. For us it’s 10.53 in the morning,” he says.

His team’s next goal was to induce the corals to spawn not once, but twice, a year in order to double the scope for research. It has succeeded with some corals, but this remains a work in progress. “The problem is that corals are like pandas,” says Craggs. “We have literally a one hour window to collect the eggs and sperm and do the research. We then have to wait a whole year to get access to those eggs and sperm again.”

This “phase-shifting” was a truly groundbreaking new technique, and one that the Horniman has since shared with at least 20 other aquaria and institutions around the world, from Australia, the Pacific Islands and the Maldives to the Middle East and Caribbean. The museum has also made it available to any interested party on the internet.

“We’ve pioneered a technique in this tiny little facility which is now world-recognised,” says Craggs. “It gets used around the world so I’m very proud of that.”

What this planned and predictable spawning in aquaria does is allow scientists and researchers to acquire, study and experiment with coral eggs and sperm in a way they seldom, if ever, could before. And different institutions are using that priceless “tool” in different ways.

Some - like The Florida Aquarium in Tampa - are using it to restore and rebuild reefs damaged not just by climate change, but by fishing, pollution and other human activities.

They select the hardiest and most resilient individual corals from a single species, sometimes from different geographical zones, and induce them to spawn in captivity. They then fertilise them through a coralline version of IVF, and let the ensuing polyps grow to a certain size and strength in artificial conditions before replanting them on struggling reefs.

“This helps future-proof that restoration strategy because you’re helping bring new genetic diversity to the population you’re planting out,” says Craggs.

Keri O’Neil, The Florida Aquarium’s director and senior scientist, told the Telegraph that “Craggs’ “groundbreaking work in coral reproductive biology has truly revolutionised how we approach conservation and research. His innovative techniques for predictably inducing coral spawning in human care have paved the way for unprecedented advances in coral restoration.”

Michael Webster, an environmental studies professor at New York University, added that successfully breeding corals in captivity was a “critical first step” towards producing corals capable of surviving stressful conditions.

But the Horniman and some other institutions are going a step further. They are experimenting to see whether they can cross different species to produce a hybrid coral better able to withstand the warming seas. Craggs has recently discovered, for example, that he can cross-fertilise one species of coral from Australia with another from Fiji.

He is at pains to stress that these genetically-modified hybrid corals will not be planted in the oceans lest they supplant or destroy existing species. The work is a “safeguard to find out what’s possible”, he says. “We’re increasing the available tool box for use in the worst case scenario”.

But neither developing hardier versions of existing species, nor creating more resilient hybrids, is likely to save the world’s corals if humanity fails to tackle climate change, so Craggs and his team are also working on a Doomsday solution with shades of Jurassic Park: the cryo-preservation, or deep freezing, of coral sperm to give future generations the chance to recreate coral long after it has gone extinct.

There are two other scientists working at the Horniman on the day the Telegraph visits. They are Tullis Matson, the ebullient founder and chairman of a company called Nature’s Safe, and Debbie Rolmanis, his chief operating officer.

To date their company has frozen the sperm or tissue of 256 species of animal ranging from the southern white rhinoceros and Asian elephants to the extremely rare and critically endangered mountain chicken frog which is found only on the Caribbean islands of Montserrat and Dominica. That material is stored at a temperature of minus 196 degrees in a top-security ‘biobank’ in Whitchurch, Shropshire. Matson likens it to a “nuclear bunker” with its concrete roof, steel doors and CCTV cameras.

On this particular day Craggs rushes the ‘bundles’ from the spawning coral - a species called Acropora kenti - down to the tiny lab where the two biologists are waiting in white coats. There Craggs gently shakes the tube containing the ‘bundles’ until they burst, releasing their eggs and sperm. Matson and Rolmanis then siphon off the sperm as it sinks beneath the eggs, and swiftly freeze it using liquid nitrogen.

Scientists in the US have managed to cryo-preserve coral sperm before, but this is the first attempt to do so in Europe. “It’s unbelievably exciting,” Matson exclaims.

Two days later Craggs calls him with good news. Of the Acropora kenti sperm only eight per cent were still able to fertilise eggs after being frozen and unfrozen, but of the sperm of another species - Acropora millepora - 45 per cent could do so.

Matson is thrilled. “This is truly groundbreaking,” he tells me on the telephone. “It’s incredible, it really is…We have dealt with sperm cryo-preservation for 30 years, but this has to be one of the highlights without a shadow of a doubt.

“It’s not just the fact that we’ve managed to freeze coral sperm and thaw it out and get embryos. It’s the implications of this for the future of coral. We’re just at the start of something extra-special in cryo-preservation of coral.”

The next challenge is to freeze coral eggs, so the frozen sperm will have something to fertilise, and for that Matson must wait for next year’s spawning season unless Craggs can dupe his corals into spawning earlier. But what is a year when you’re looking a century or millennia into the future, to a time when humanity has hopefully learned to live with nature and not destroy it?

“If you can freeze eggs and freeze sperm you can hold the genetics of that coral down pretty much indefinitely until it’s needed in ten, twenty or a thousand years. If we can crack this it will be as good as the day it’s frozen,” says Matson.

“We are the ultimate fall back if all else fails,” adds Romalis. “For some coral reefs bio-banking them is their only chance of survival because they’re being so depleted in the wild.”

Back in South London, Craggs talks modestly about his team’s achievements. He stresses that he works in collaboration with counterparts in many other countries, and relies heavily on grants and partnerships. But scientists and researchers now fly in from all parts of the globe to visit the Hormiman aquarium and study Craggs’s work, and he regularly flies off to far-flung conferences to talk about the remarkable breakthroughs he has achieved since 2012 in his improbable South London base.

“I look back on what we’ve achieved in that time and it’s absolutely extraordinary,” he concedes shortly before flying off to a conference on ‘reef futures’ in Mexico. “We have so many visitors come from all over the world, and they go ‘I literally can’t believe what you’re able to do in a tiny corridor’.”